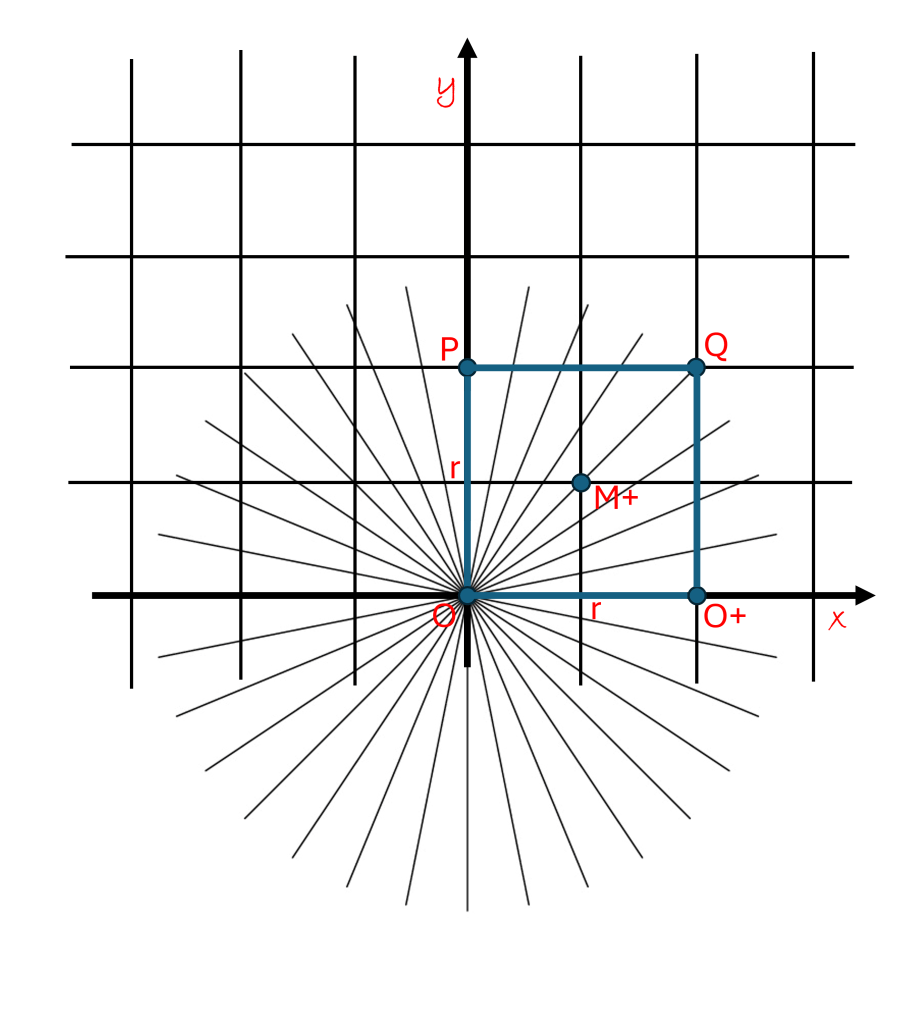

In the last post’s “cartesian grid” diagram, if you remember, the radial lines went through the point P. By reflection symmetry, I can reflect these radial lines onto any cartesian grid point I want. In the diagram above, I decided to reflect the radial lines so they now radiate from point O. I now choose point O to be the reference point.

I choose one of the “cartesian” directions to be from the reference point O to the point O+, I will call this direction the positive “x” direction, labeled by the red script “x”. I call this line the “x” axis, shown as a bold horizontal line in the diagram.

The second “cartesian” direction I choose to be from the reference point O to the point P. I call this direction the positive “y” direction (as customary), and label it with a red script “y”. This vertical line in the diagram is called the “y” axis and is bolded. There are always two perpendicular independent directions I can choose in a 2-D space. The axiom of choice allows me to choose whatever reference point I want and whatever two reference directions I want. As mentioned before, the right to choose is one of the fundamental concepts of math.

Alright, let’s talk money. In 1-D space, distance is everything, it is the most valuable asset, but in 2-D, distance alone is not worth anything. A piece of land that is 10 meters long has no value until you know how wide it is. The real estate of 2-dimensional space is called “area”. Area is measured by how many squares, or fractions of squares can fit within a given border. The number of squares determines the value.

In the diagram, we form a square by taking the segment O O+ (of length r) and the perpendicular segment O P (also of length r) and reflecting them through M+ to form the opposite sides P Q and O+ Q. Note that we found a point Q that is exactly the distance “r” from both the “x” and the “y” axis. This square (in green) now has value, it is the real estate of 2-D space.

We have seen that the whole 2-dimensional space can be “tiled” with the squares of a cartesian grid. The number of “tiles” within a boundary determines the area. For example, in the diagram above, the green r x r square has 4 cartesian tiles inside. Each side has 2 tiles and 2 x 2 = 4 tiles. Since we could shrink the size of the tiles, we could also fill the square with lots of tiny tiles. From this, it can be deducted that the area of the square is found by multiplying the length of the square by the width of the square (r x r = r2).

The area of the green square in the diagram is r2. In 2-dimensions, the “real estate” or area is always measured as a distance times a distance, like a square meter, or a square foot. In 2-D, a line segment alone has no width, and so it has no area, and thus line segments have no real value in 2-D space.

In concept, you can fit an infinite amount of parallel line segments into a square no matter how small it is. This becomes clear when we recall the same concept in 1-D space to show that an infinite number of points can fit between any two points on a line segment, no matter how small.