All the concepts that we have discussed so far can be expanded into new dimensions. We have only been looking at two dimensions so far, and yet we live in a world of 3 physical dimensions. Although mathematically we don’t have to stop at 3 dimensions, we could expand the same concepts to work in as many dimensions as we want. First, let’s start by generating a 3-dimensional space from the 2-dimensional space we have been working in.

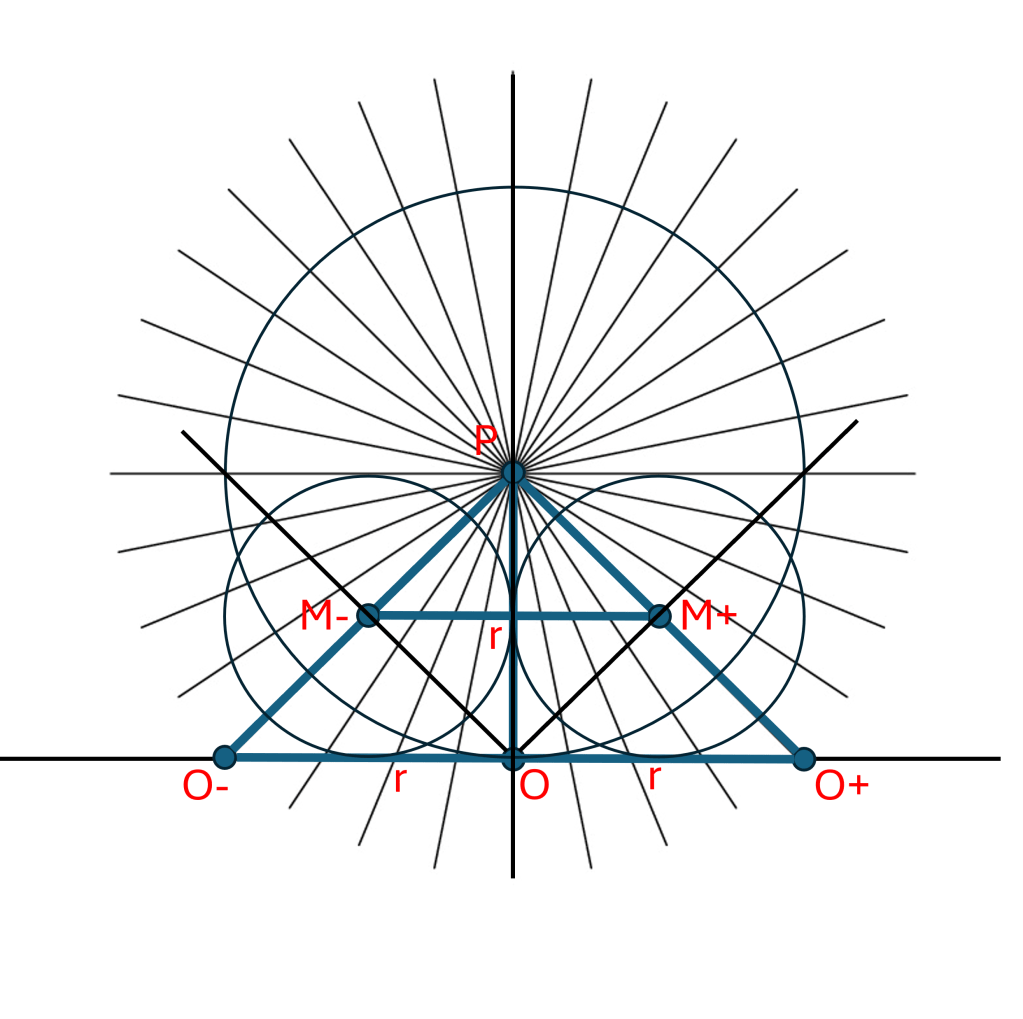

Do you remember how we generated new dimensions? Look back to the expanding dimensions post to refresh your memory. Take the 2-dimensional x-y plane where we have been working and find a point “P” that is NOT in it. Now imagine line segments between every point in our 2-D space (x-y plane) and the new point P. Find the point on the x-y plane (2-D space) that forms the line segment with the shortest distance to P and label it “O”. Call this minimal distance “r”.

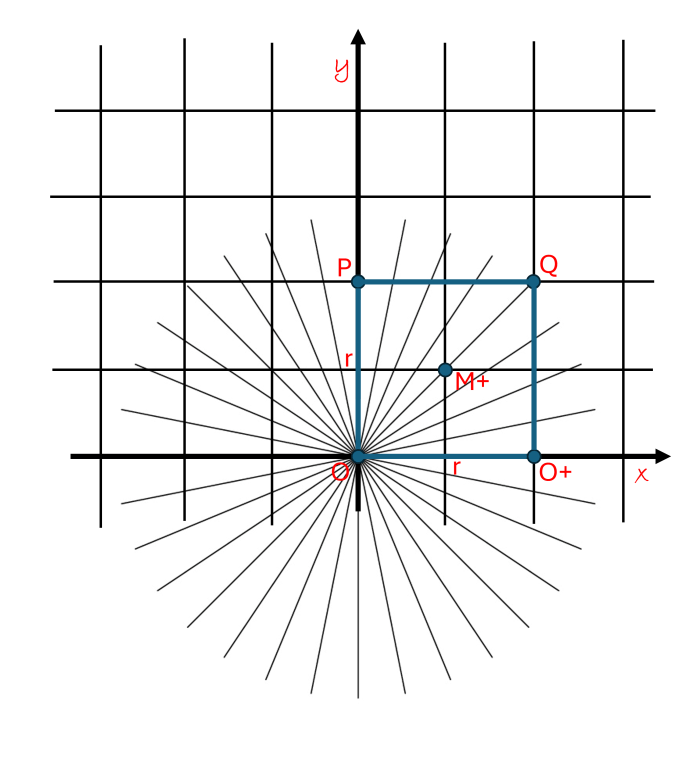

We can choose the point O to be the origin on the x-y plane and pick an x-direction for the x axis, which also determines the direction for the y-axis. We can now use the same diagram above, the same procedure (and a bit of imagination) to generate a 3-D space from a 2-D space with one observation. In our original 1-D space there were only two directions from the point O, negative (O-) and positive (O+). In the 2-D space, there are an infinite number of directions pointing away from the point O, and each direction is indistinguishable from any other direction.

We can use this rotational symmetry to generate our 3-D space. Imagine that you printed the diagram above and on a sheet of paper and placed it so that the point O is on the origin of the x-y plane, the point P (the new point) is above the x-y plane, and make the x-axis go through the O+ point. The sheet (plane) of our diagram would now be perpendicular (vertical) to the x-y plane. The same argument holds that since the O-P segment is the shortest one that connects the x-y plane it is an axis of symmetry.

We call this new O-P direction the “z” axis. Now imagine rotating this diagram around the z axis. The O+ point would trace out a circle on the x-y plane, and touch every point on the plane that is a distance “r” from point O. The distance from every one of these points on this circle would also be the same distance from P. The segments P-O+ would sweep out the surface of a cone as we rotated the diagram around the z axis, and parallel lines would sweep out parallel planes along the z axis. We can rotate our sheet of paper around the z-axis to any angle and the cross section would still remain the same. Can you see it?

We can use the same trick as before, we can imagine that these parallel planes are mirrors facing each other that will reflect an infinite array of parallel planes to the x-y plane along the z axis, thanks to reflection symmetries. We can also make an infinite set of parallel planes along the x axis, and along the y-axis by processes similar to those we did before in 2-D to make a cartesian “grid” of planes and fill in all the gaps.

Note that the line segment O-P does not move when we rotate the diagram around it. It is stationary under rotation. Now we have fully leveraged the rotational and reflectional symmetries of 3-D space. We can pick any axis of rotation (a line), rotate the universe around it, and the universe will remain unchanged, only our vantage point changes.

As always, we can pick any point in 3-D space to be the reference point (origin). And any 2 perpendicular directions (an x and y axis) can be chosen to define a 2-D plane, and the third direction (z axis) perpendicular to this x-y plane is determined. These three directions define how we write points in this new 3-D space.

In cartesian coordinates, the vector (x, y, z) can label every point and (Dx, Dy, Dz) can label every direction.

Lines in 3-D space can be defined by:

(x, y, z) = (x0, y0, z0) + (Dx, Dy, Dz)*S

Where (x0, y0, z0) is the point of origin for the line, (Dx, Dy, Dz) is the direction of the line, and “S” is the distance along the line from the origin. At this point, this notation should not be difficult or surprising. The above is also an equation for a sphere if you hold S constant to be the radius and vary the direction.

There might be some questions on how you can determine directions in 3-D space. Similar to 2-D space, the direction vector always has a length of 1 unit:

Dx2 + Dy2 + Dz2 = 1

A natural way to determine directions is by using your head. Stand facing North (the x-axis), now rotate your head an angle “Axy” to the left (West towards the y-axis). You can determine every direction on the x-y plane with this angle Axy (between -180 and 180 degrees). Now tip your head up an angle “Az” off the x-y plane (between -90 and 90 degrees). Varying these two angles, you can now look in any direction possible in 3-D space.

This is also how we locate positions on the spherical surface of the earth. We place an imaginary observer in the middle of the earth and have it “face” 0 degrees longitude and 0 degrees latitude (the x-axis). The Axy angles are degrees of longitude as the observer rotates its head around the north pole (z-axis), and the Az are degrees of latitude as the observer tips its head up and down. Using this scheme the observer can look at any place on the surface of the earth given a longitude (Axy) and latitude (Az).