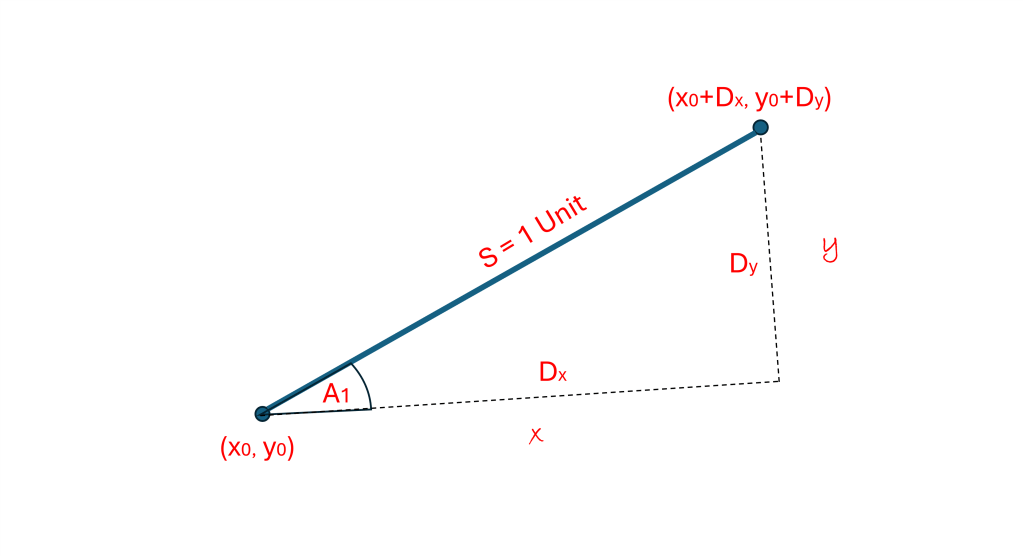

We have seen the power of the dot products between two direction vectors. We have shown that the dot product between two perpendicular directions is zero. We will review this in two dimensions, because it is easier to see. Using our head reference the nose direction in 2-D is N:(Dx, Dy) and the Left ear direction is L: (-Dy, Dx):

N.N = (Dx, Dy).(Dx, Dy) = Dx2 + Dy2 = 1

N.L = (Dx, Dy).(-Dy, Dx) = -Dx*Dy + Dy*Dx = 0

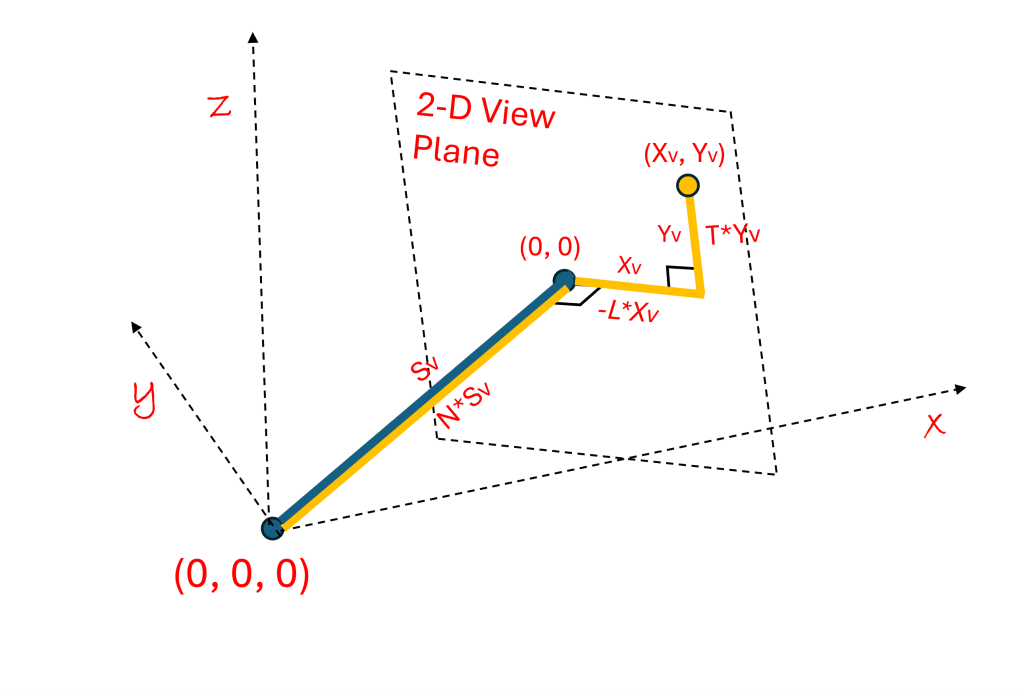

We have also seen that we can travel to any point in 2-D (x, y) by traveling in the N direction a distance SN and then turning left and traveling in the perpendicular L direction another distance SL:

(x, y) = N*SN + L*SL

And then we used the power of the direction dot products to see what happens when we dot these direction vectors with any point (x, y) in the 2-D space:

N.(x, y) = N.(N*SN + L*SL) = N.N*SN + N.L*SL = 1*SN + 0*SL

= SN

L.(x, y) = L.(N*SN + L*SL) = L.N*SN + L.L*SL = 0*SN + 1*SL

= SL

Written in concise dot product notation:

[N, L].(x, y) = (SN, SL)

This means that dotting these “head direction vectors” (N, L) with any point gives you back the coordinates of the point in the “head frame of reference” (SN, SL), the distance traveled in the Nose direction and the distance traveled in the Left direction to arrive at the point. From the last post, in 3-D, we saw that SN is the distance from the Nose to the perpendicular View Plane where the point lives.

We can conclude that in any dimension, if we dot the Nose direction (N) with any point we get back the “nose coordinate” in the “nose frame of reference” (SN):

N.(any point) = SN

It might take a few moments of thought for this to sink in, but when it does, we start to realize that we can convert any point into the “nose frame of reference” no matter where our nose is pointing. It is like rotating the reference frame into any direction we want and converting the coordinates into this “nose frame of reference”.

We might ask what happens when we dot two direction vectors together that are not perpendicular. Suppose we have two Nose directions (N1 and N2) in 2-D:

N1 = (Dx1, Dy1)

N2 = (Dx2, Dy2)

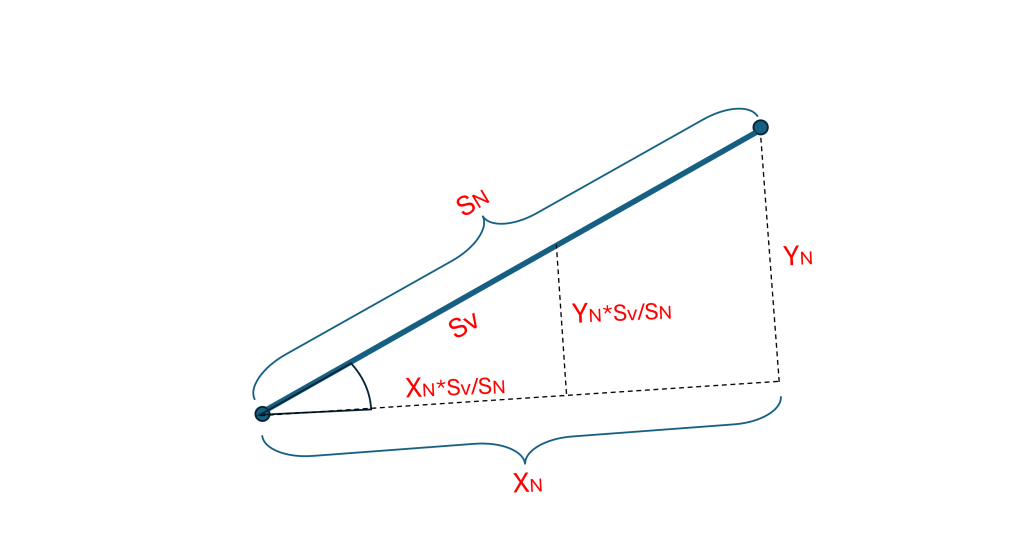

Since any point (x, y) can be expressed in the N1 frame of reference, (Dx2, Dy2) can also be written in the N1 frame:

(x, y) = N1*SN + L1*SL

N2 = (Dx2, Dy2) = N1*SN + L1*SL

Refer to the diagram above for clarification. Now we can easily see what happens when we dot N1.N2:

N1.N2 = N1.(N1*SN + L1*SL) = N1.N1*SN + N1.L1*SL

= SN

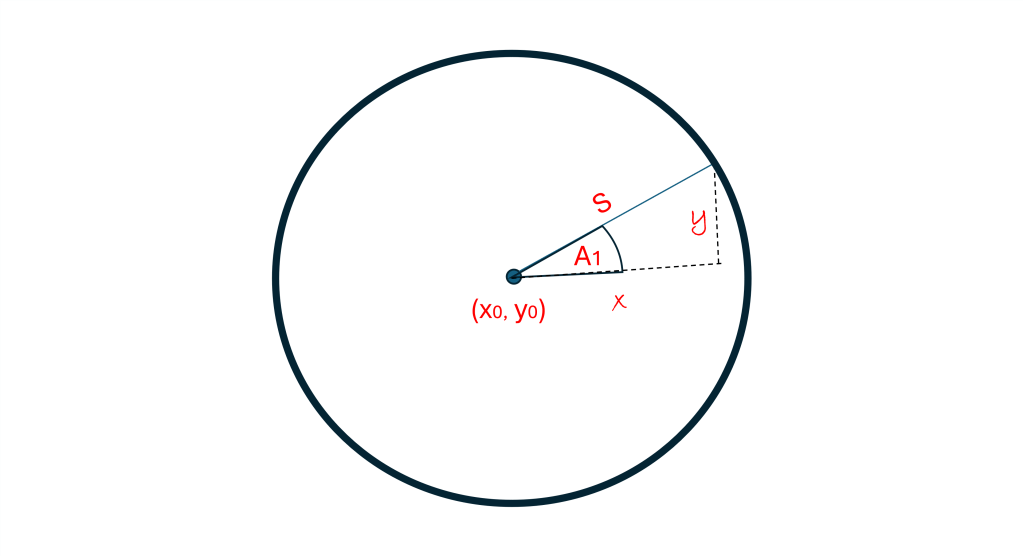

Now from the diagram we also can see that SN is just the Cos(A) because the length of N2 is 1, where A is the angle between the two directions:

N1.N2 = Cos(A)

So, when we dot two direction vectors together, we get the Cosine of the angle between them. This is consistent with what we have seen, because when the two directions are the same, A = 0 degrees, and when they are perpendicular, A = 90 degrees. Cos(o) = 1 and Cos(90) = 0 this is consistent with what we have shown when dotting direction vectors together so far.

I have earned some good money from knowing this. On one occasion, a ship captain wanted me to find the distance between two points in the ocean given the longitude and latitude of each point. Recall that the longitude and latitude is the same as the “head direction” as seen from the center of the earth. (Axy1, Az1 and Axy2, Az2).

I realized that if I could find the angle between these two “head” directions (A), I could find the distance between the two points along the surface of the earth. Since I know that the circumference of the earth (CE), the distance between the points is CE*(A/360). I found N1 (the direction vector to the first point) and N2 the direction to the second point, dotted them together to find the angle: N1.N2 = Cos(A), and took home a large check (he still uses it to navigate). Could you fill in the details?