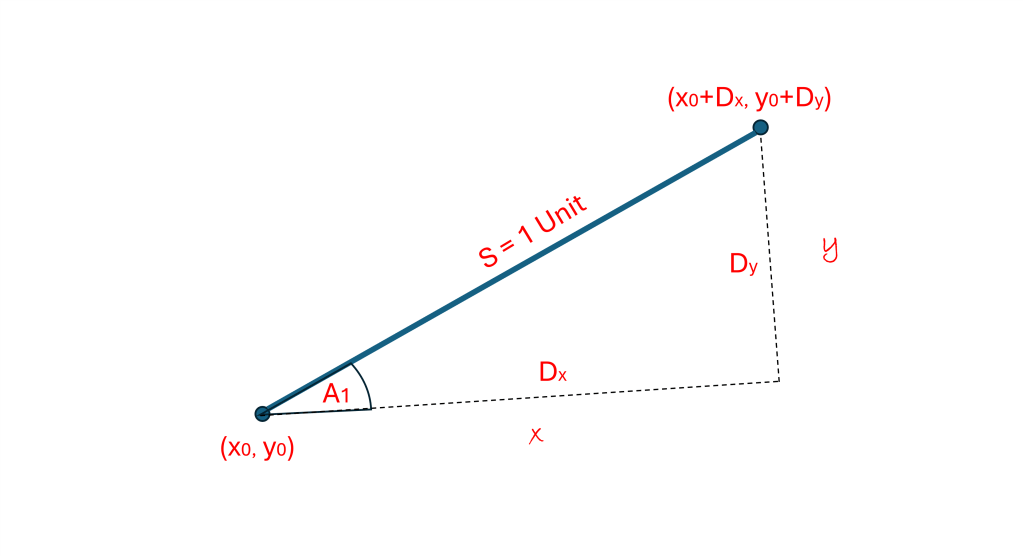

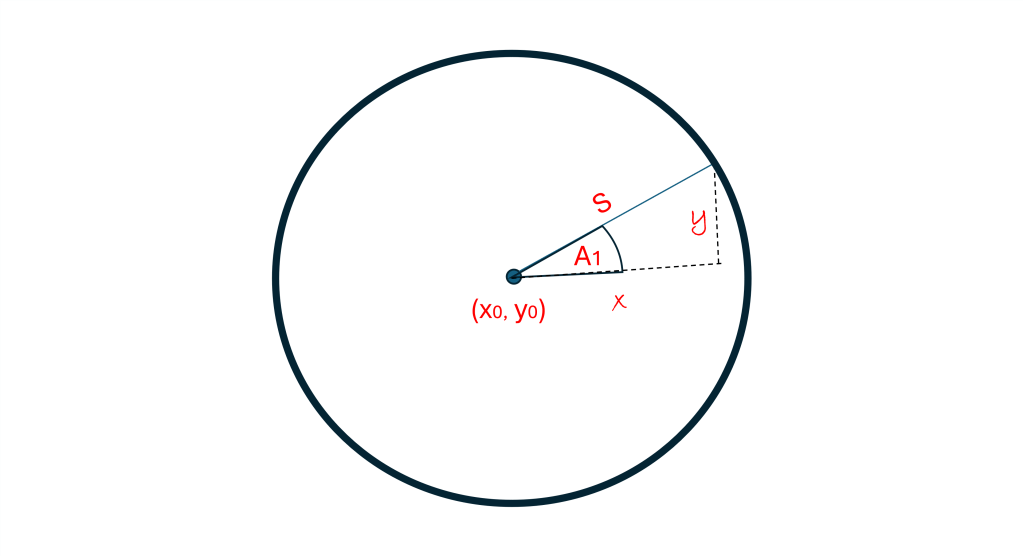

Soldiers and airplanes in unfamiliar places need to find their way around. They can do this with methods similar to what we have already discussed. They receive instructions to go first in a certain direction (Dx1, Dy1) for a certain distance S1, and then to change course to another direction (Dx2, Dy2) and keep going for a distance S2. This same pattern can be followed for many different directions and distances. This discipline is called orienteering. Soldiers are trained to find directions with their compasses and measure distances with the number of steps they take.

With our new vector notation, we can say the same thing in math language:

(x, y) = (Dx1, Dy1)*S1 + (Dx2, Dy2)*S2

Which says that the point of our destination (x, y) can be found by going in the direction (Dx1, Dy1) for a distance (S1) and then going a direction (Dx2, Dy2) for a distance (S2). Notice that to find our destination (x, y), we just add these two vectors together. It is just like piecing together lines to form a path.

Any destination (x, y) is determined by just adding together all the lines (vectors) that form the path in between. In the example above, there were only 2 directions and distances (lines), but we could keep on going for as many vectors as we want, adding on lines, one line after another until we arrive at our destination.

It is helpful to define yet another notation that is even more compact.

(x, y) = (Dx1, Dy1)*S1 + (Dx2, Dy2)*S2

can be written

(x, y) = [(Dx1, Dy1), (Dx2, Dy2)] . (S1, S2)

The dot “.” between the two vectors is called a “dot product”. In the case above the dot product means you multiply the first direction vector in the square brackets [1,2] with the first distance in the round brackets (1,2) and do the same with the second direction vector and second distance and then add them both together.

This new notation might seem a bit mysterious at first, but it does make things clearer later on. The dot product is one of the most fundamental operations of “linear algebra” which is the math that tells you where you end up when adding together a bunch of lines (vectors) to form a path.

We do something similar to write the (x, y) coordinates of a point in our cartesian plane. Let’s look at the point (3, 4), we can get there by walking along the x-direction 3 units, then turning left 90 degrees and walking in the y-direction 4 units:

x-direction: (Dx1, Dy1) = (1, 0)

y-direction: (Dx2, Dy2) = (0, 1)

Then using the “dot product” notation we discussed above:

(x, y) = [(Dx1, Dy1), (Dx2, Dy2)].(S1, S2)

(x, y) = [(1, 0), (0, 1)].(3, 4)

= (1, 0)*3 + (0, 1)*4

= (3, 0) + (0, 4)

= (3+0, 0+4)

= (3, 4)

We find that we end up at the point (3, 4). This is also one way in the cartesian coordinates that we can define the location of a point. So, the [(1, 0), (0, 1)] vector when “dotted” with any two distances (Sx, Sy) brings you to the point (x, y) = (Sx, Sy).

(x, y) = [(1, 0), (0, 1)].(Sx, Sy) = (Sx, Sy)

Do you get the point? You are starting to see the “language” of the dot product. In math language a vector of vectors is called a matrix and [(1, 0), (0, 1)] is called the “identity matrix”, because when you dot it with any vector you get back the same vector.

The dot product can be applied to any two vectors of the same size. This concept is used all over the place. Here is an interesting example, we can use the dot product notation to write down the number 365 (in decimal) starting with the vector (3, 6, 5):

(3, 6, 5).(100, 10, 1) = 3*100 + 6*10 + 5*1 = 365

This is how we write numbers (in base 10). It is read like this: 3 in the 100’s column, 6 in the 10’s column and 5 in the one’s column, added together, normally written “365”.

We could also use it to find the number of seconds from midnight to 04:35:20am from the vector (4, 35, 20):

(4, 35, 20).(3600, 60, 1) = 4*3600 + 35*60 + 1*20

= 16520 sec

There are 3600 seconds in an hour, and 60 seconds in a minute. I think you got the idea.