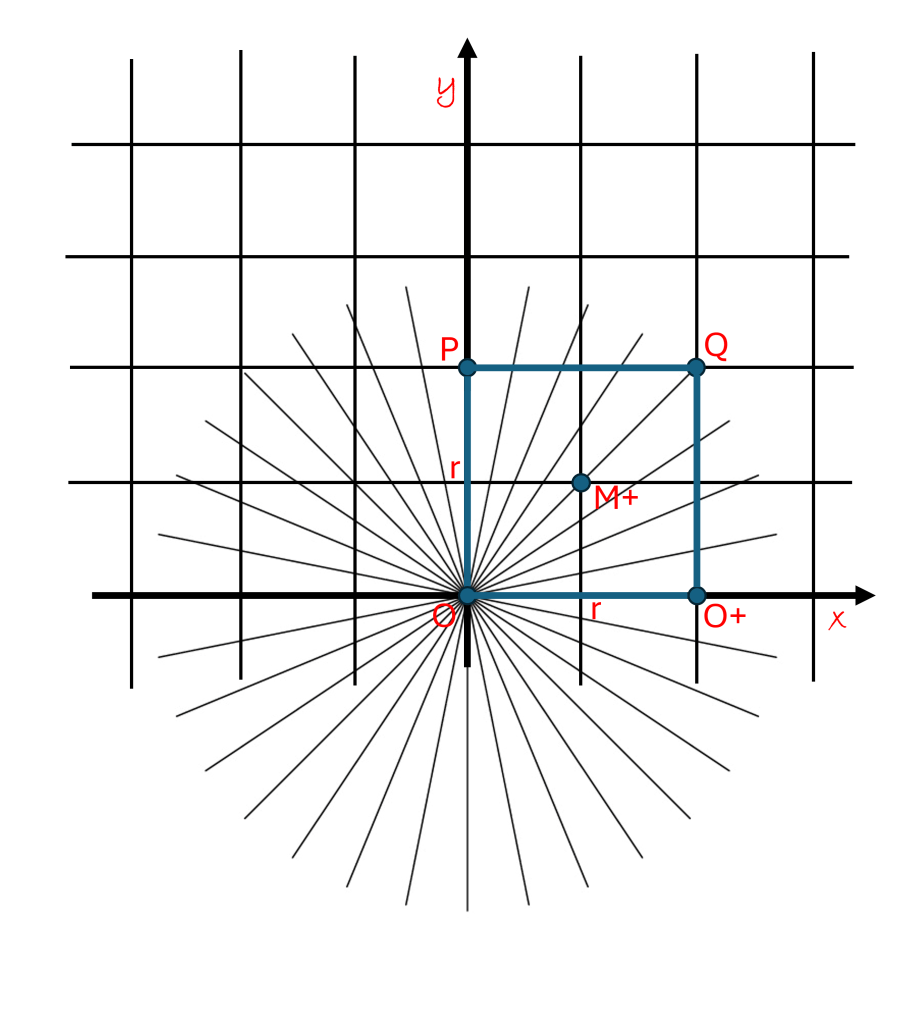

You can learn a lot about something when looking at it from a new perspective. In the diagram above we are looking at the exact same square as in the last post from a different vantage point. Again, I use my right to choose a reference point and direction. I keep the point O as my reference point, but I rotate the cartesian grid a bit clockwise.

Notice that I have not changed anything about the square, it has the same points. I have only changed the way I am looking at the square. The area of the square has not changed, it is still r2. I have just “tilted my head” a little bit. I chose an “x” direction that is not along the O O+ side of the square and the “y” direction to be perpendicular. This is certainly within my rights under the axiom of choice.

From this perspective, however, the way I measure the area of the square is a bit different, I cannot “tile” the square with the cartesian tiles in this direction without “cutting off” the corners of the tiles. From here grows the whole field of trigonometry. I need to rotate my ruler to measure distance from any point and in any direction in 2-D space.

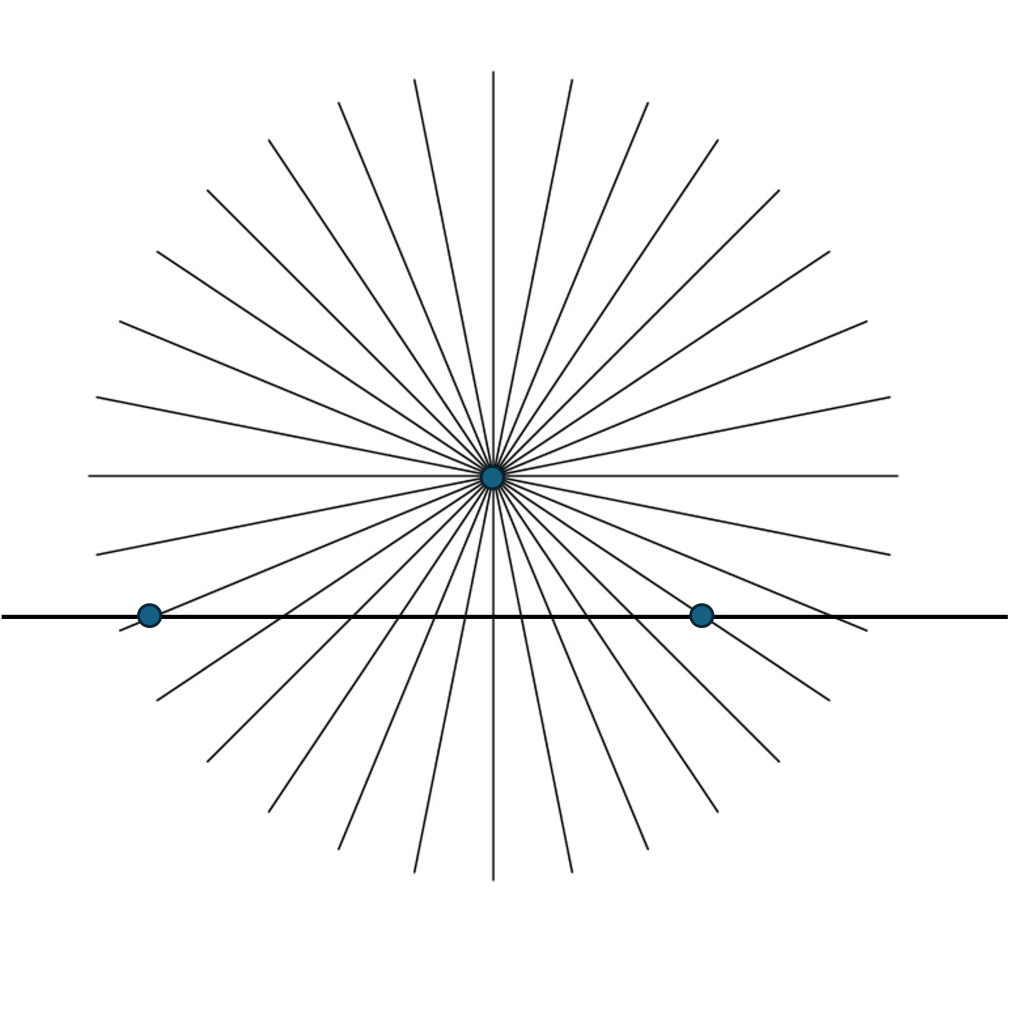

In the diagram above, I am looking at the “bottom” line segment of the square, O O+, from this new perspective, I have also modified the grid spacing a bit for better clarity. In this diagram, I found the “coordinates” of the O+ point by finding the perpendicular distance from both the x and y axis, as is customary. The distance away from the y axis is labeled “x”, and the distance away from the x axis is labeled “y”.

It is obvious from the diagram that, by parallel sides, the respective distances from O+ form a rectangle with one side a distance “x” along the x axis and another side a distance “y” along the y axis. These distances are called the cartesian “coordinates” of the point O+. It is also obvious that the area of this rectangle is x times y, written as x*y ( we use “*” to mean “multiplied by” for clarity).

If I now choose the O+ point to be the point of reference and chose the “y” direction to be down and “x” direction to be to the left, as shown by the yellow script “x” and “y” in the diagram, I basically would have chosen to look at this same rectangle from an “upside down” perspective. By flipping the diagram upside down, you can see that the rectangle and O O+ line segment looks exactly the same from this perspective.

This shows an important symmetry of the rectangle. It also shows that the area of the triangle on the top half of the rectangle is exactly the same as the area of the triangle on the bottom half. Or to say, the segment O O+ cuts the rectangle in half. Thus, the area of both triangles is ½ * x * y. This also shows that the angles of both corresponding triangles are exactly the same. We will talk about this later.

The equivalence of areas (the real estate of 2-D), regardless of our choice of reference point and direction, gives us a way to “rotate” our ruler into any angle and direction. This relation was found by Pythagoras many millennia ago and is called the Pythagorean theorem.